by Karen Lee

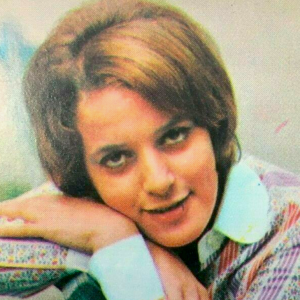

Janet Reno (July 21, 1938-Nov 7, 2016) was the first woman to serve as US Attorney General (AG) under the Clinton administration. Some key events that occurred under her tenure as AG were: 1) authorizing immigration officers to remove 5-year-old Cuban boy Elian Gonzalez, by gunpoint, from his Cuban-American family to return him to his biological father in Cuba; 2) the FBI siege and subsequent assault on David Koresh’s Branch Davidian compound, resulting in 76 deaths, 25 of which were children; and 3) and the capture and convictions of “Unabomber” Ted Kaczynski, and Oklahoma City terrorists Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols.

Reno was born in Miami, Florida to Henry Reno, a police reporter in Dade county, and Jane Reno, a naturalist who wrestled small alligators. Reno grew up as the oldest of four siblings, living on twenty-one acres bordering the Everglades, where her mother constructed their family home, despite having no building experience and digging the foundation with her hands and a shovel. Her mother’s strength and independence had a huge impact on the persona of Janet, who roamed the property with peacocks, alligators and other flora and fauna in their Everglade home. After graduating high school in Miami, Reno attended Cornell University and graduated in 1960 with a degree in chemistry. She applied to Harvard Law School and was admitted, graduating in 1963, one of a small cadre of women within a class of 500 men (Hulse, 2016).

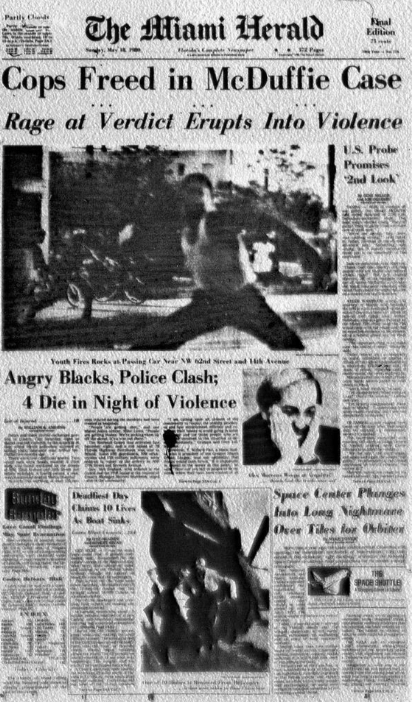

Reno began serving in government as general counsel to the Judiciary Committee of the Florida House of Representatives in 1971. Her focus was to help overhaul the Florida court system which inspired her to campaign for her own state legislative seat. Unfortunately she lost to a Republican candidate due in part to the reelection win of President Richard Nixon. Richard Gerstein, then state attorney for Dade county, offered Reno employment on his staff, and within a few years she was Gerstein’s chief assistant. Gerstein resigned in 1978 after serving 21 years, and Gov. Rubin Askew made Reno interim state attorney. She was the first female to hold that office in Florida, maintaining stewardship of a large jurisdiction. Reno persevered through many murder, drug and corruption cases. She was accused of being “anti police” in 1980 after she prosecuted five Miami police officers in the fatal beating of a black insurance executive, Arthur McDuffie, after a traffic stop. She asserted that the officers tried to make his death look like an accident. Unfortunately the officers were acquitted by an all-white jury, which led to four days of rioting in Liberty City, Miami’s predominantly black neighborhood (Hulse, 2016).

When Liberty Burns (2020) Documentary directed by Dudley Alexis

After the rioting started, Reno immediately began outreach efforts into Miami‘s black neighborhoods to help quell racial anger from yet another police lynching. The riot in Liberty City was the first racially motivated riot since the Civil Rights era and was the most destructive up to that point. The unrest claimed 18 lives and the damages incurred totalled eighty million dollars. The National Guard were called in to restore order.

Reno experienced conflicting responses from Miami’s African-American community after the police acquittal, with many accusing her of having a bias against the black community because of the exoneration. Many African-American leaders asked for her resignation, and Jesse Jackson went to Miami to advocate for her to step down from her position as state attorney. The repercussions from the acquittal inspired Reno to speak more directly to Miami’s black communities, and she dedicated more time to understanding the concerns of Miami’s black citizens. A noteworthy issue Reno was passionate about was the large number of “deadbeat dads.” This issue moved her to delegate special departments in her office to provide justice for single mothers and by the next election cycle in the mid 80s, Reno’s credibility in the Dade County black communities was redeemed and she ran without any opposition (Sarig, 2007).

Luther Campbell, aka Luke Skyywalker, could not recall if he took part in the Liberty City riot, or if he was a looter. The Miami Bass sound was popular in Miami, stemming from 1979 when Luke Skyywalker started the genre with his group, Ghetto Style DJs. In the 1980s, 2 Live Crew, produced by Luke Skyywalker, led Miami Bass into national mainstream culture (Sarig, 2007).

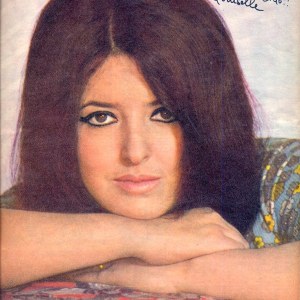

Reno’s popularity among black women was especially high. Luther Campbell supported Reno by running a voter drive during the election season. Campbell’s cousin Anquette Allen came onto the scene with a “beef” track to 2 Live Crew’s “Throw the D,” with “Throw the P.” She was the leader of an all-female Miami Bass trio named Anquette, along with rappers Keia Red and Ray Ray. Following their early singles in 1986, they released an LP called Ghetto Style the following year, along with their Liberty City anthem, “Shake it – Do the 61st.” Anquette then came out with “Janet Reno” on Luke Skyywalker records in 1988.

In “Janet Reno” Anquette raps about Reno when she was Florida State Attorney as a heroine fighting for single mothers’ rights. She was an advocate taking from child support evading deadbeat dads and giving back to hard working single mothers in Miami. Anquette reminds ladies to, “Make sure that you got some protection; think twice the next time before you jump right in the bed; take a minute out to put a rubber on your head.” Anquette’s advocacy aimed to protect the “P” and their song “Janet Reno” empowered single mothers along with Reno’s child support policies. The chorus was to the tune of “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” sung “Janet Reno comes to town collecting all the money; you stayed one day then ran away and started actin’ funny; she caught you down on 15th Ave, you tried to hide your trail; she found your ass and locked you up, now who can’t post no bail.”

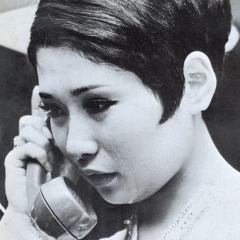

The song debuted during the November 1988 election cycle. After Reno heard the song she was interviewed by the Miami Herald. She explains that she “did not understand all of it but it says we all have to take care of our own, if you bring a child into the world, you have to be prepared to face up to the responsibilities.” Reno clearly had no intention of dancing to “Janet Reno” (Tomb, 2016).

In the next election cycle a conservative Christian lawyer, Jack Thompson, who was involved with the religious right in Dade County from Coral Gables, posed to de-seat Reno from her ten year appointment. Thompson’s campaign attacked Reno, openly questioning Reno’s sexual orientation and trying to “out” her publicly. In Washington DC, congress members contested and surmised Reno was a Clinton flunky, and adversary. Heteronoramtive bigotry attempted to shame her and labeled her as a drag queen, a lesbian or a queer. Reno’s sister, Maggie stated she was a “large person with boots on.” (Paterniti, 2016) Reno was again re-elected by a large margin but neither Thompson nor his followers stopped their campaign against Reno after their defeat.

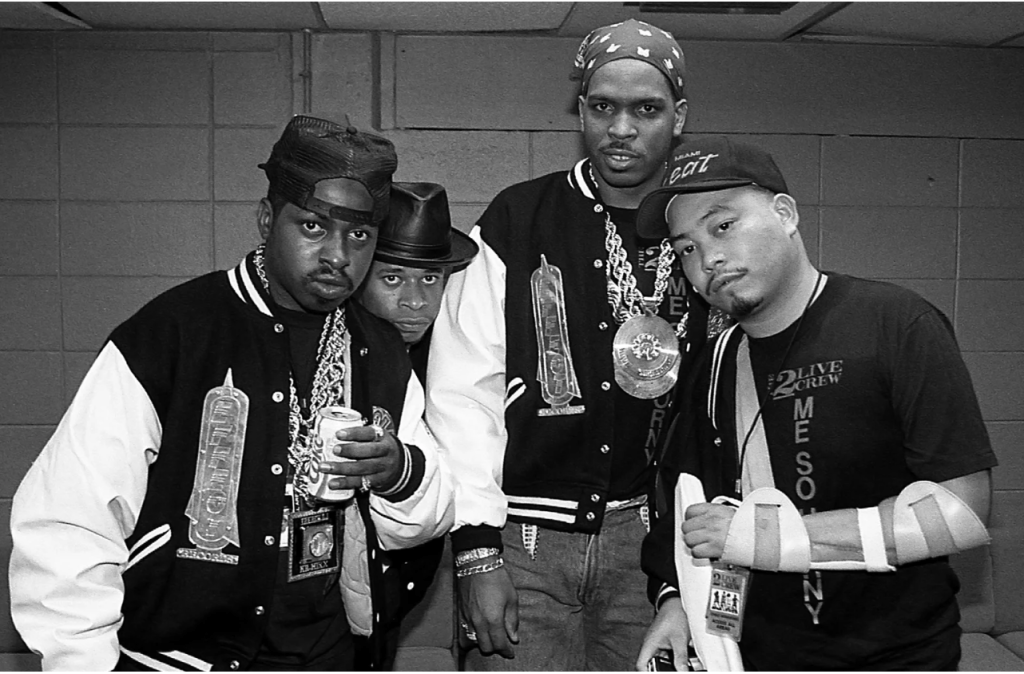

In 1989, 2 Live Crew, on Luke Skyywalker Records, released one of the most sexually explicit recordings ever sold. As Nasty As They Wanna Be offered listeners the dirtiest, nastiest most depraved songs depicting sexual aggression and XXX-rated racist humor. One track above all became a cultural flashpoint: “Me So Horny,” with its Vietnamese vocal sample from Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, still makes Asian women cringe, wince, and experience homicidal ideation when strangers say that catch phrase to them in a “Vietnamese” accent. “Me So Horny,” one of the tamer songs on the record, went to No.1 on the Billboard Hot Rap Singles chart. 2 Live Crew became national news, even appearing on the popular nationally syndicated Arsenio Hall Show. They were targeted by Tipper Gore’s Parent Music Resource Center (PMRC), As Nasty As They Wanna Be responsible for corrupting American youth morals. If only they’d had warning stickers to inform their children’s purchasing decisions. In the end, Tipper Gore was the best marketer of As Nasty As They Wanna Be and likely broadened its appeal exponentially, especially among white Christian teenage boys. Christopher Won Wong, cofounder of the band, was the first prominent Asian-American rapper, he was Trinidadian and Cantonese. Other musicians in the group were DJ Mister Mix (David Hobbs), Amazing Vee (Yuri Vielot), Luther Campbell (Luke Skyywalker) and Brother Marquis (Mark Ross).

2 Live Crew were used to controversy from their previous releases, 2 Live is What We Are (1986) and Move Somethin’ (1988). These albums were so nasty record store clerks of the big chains began to experience parental backlash. Jack Thompson, the guy who’d just lost to Reno, took it upon himself to join with the American Family Association to use his political connections to target and ban As Nasty As They Wanna Be. Thompson worked with Florida’s Governor Bob Martinez in a campaign to ban the album statewide. Martinez advised Thompson to obtain an obscenity level for the album in local jurisdictions, so Thompson enacted Sheriff Navarro in Broward County, neighboring Dade, which enabled a ruling from County Court Judge Mel Grossman, to terminate sales of As Nasty in Broward county. 2 Live Crew countered with a censorship suit filed against Navarro for violation of their first amendment rights. 2 Live Crew went to court in June, supported by intellectual giants like African-American scholar Henry Louis Gates, who taught at Yale and Cambridge. Gates testified 2 Live Crew’s songs were versed in the African American oral tradition of parody, perhaps being explicit but not obscene. Unfortunately U.S. District Judge Jose Gonzalez ruled As Nasty was obscene, and 2 Live Crew was the first band in U.S. history to have a popular recording banned (Sarig, 2007).

2 Live Crew, now nationally infamous, continued to play shows. Led by Luke Skyywalker, the rap group played shows at adults-only clubs which ended in their arrest. Road managers posted their bail immediately and the band was off to the next venue. Record stores continued to sell As Nasty under the table and undercover police officers would arrest and fine record store owners who sold the album in Broward County. As Nasty, sold more than 2 million copies worldwide but touring became increasingly more difficult for the band due to insurance costs because of liability from harassment from local law enforcement wherever they performed.

Luther Campbell credits Reno in being the only state prosecutor who chose not to come after 2 Live Crew because of obscenity laws. At the height of their fame in 1990, Campbell explains, “In fact she defended our right to be as nasty as we wanted to be.” Campbell formed a youth program, The Liberty City Optimist Club, and Reno was the first person to donate to the program. Reno was loved in the Miami black communities because of her advocacy in standing up for African Americans when no other politician would. Campbell states, “As Miami-Dade County State Attorney and the first woman U.S. Attorney General, Reno handled her high profile jobs with professionalism,” Campbell wrote. “She never allowed politics to dictate her decisions. Reno was a true Florida icon.” (Respers, 2016).

References

Hulse, C. (2016). Janet Reno, first woman to serve as U.S Attorney General dies at 78

Paterniti, M. (2016). Janet Reno : What you learn when you ride shotgun with the former attorney general.

Respers France, L. (2016). ‘Uncle Luke’ Campbell pens tribute to Janet Reno. https://www.cnn.com/2016/11/07/entertainment/luther-campbell-janet-reno/index.html

Sarig, R. (2007). Third Coast: Outkast, Timbaland, and How Hip Hop Became a Southern Thing

Tomb, G. (2016) Feel the beat? It’s the Janet Reno rap song https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/article113017273.html

“It goes in circles.” – Bruno S.

“It goes in circles.” – Bruno S.