“For twelve centuries we fought against China. For 100 years we fought the French. Then came the American invasion–500,000 of them–and it became a war of genocide.” — Father Chan Tin

“The Oriental doesn’t put the same high price on life as does a Westerner. Life is cheap in the Orient.” — General William Westmoreland

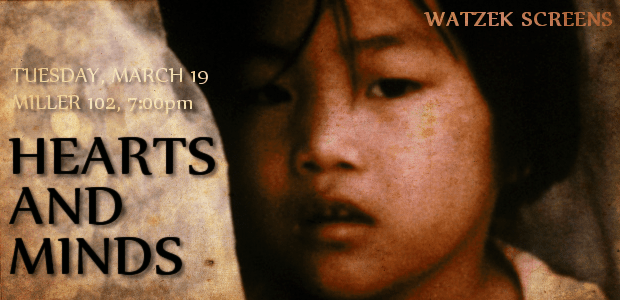

Throughout the late 70s-80s, Vietnam became the focal point for a broad range of American films, some dealing with combat (Platoon, Full Metal Jacket), some with aftermath (Deer Hunter, Coming Home, Born On the Fourth of July), others using it as a setting for adaptations (Apocalypse Now as Conrad’s Heart of Darkness). Then there was the deluge of POW films from 1983-86, with even Gene Hackman (Uncommon Valor) getting on the solider-of-fortune vigilante bandwagon. Within Reagan’s creepy and bankrupt culture of nationalism, the Vietnam “Prisoner of War” movement went into overdrive, fueled by a fervent anti-Communism permeating the mass media of 1984, the year of Reagan’s re-election. Newt Heisley’s flag image, created in the early 1970s, was suddenly plastered everywhere. In the midst of this, and perhaps as a reaction against it, new documentary forms were taking shape. These new filmmakers were social activists and balked at the notion of a so-called “balance” that they were constantly being accused of lacking. The first was Rafferty-Loader’s Atomic Cafe in 1982, an examination of Cold War hysteria told through an incredible collage of newsreels, educational films, and other “duck and cover” pop culture. The second was Michael Moore’s Roger & Me in 1989, his swan song to Ford and Flint. But both owe much to an earlier, lesser-known 1974 film that Moore has called “not only the best documentary I have ever seen, but maybe the best movie ever.” That film is Peter Davis’s Hearts & Minds.

The impact of the Vietnam War on U.S. policy is well known: it made conscription unsustainable, drafted soldiers being too much of a liability both on the battlefield and once returned home. Reagan’s administration realized indigenous mercenaries like the Contras could be financed, armed, and trained to terrorize their own pro-democratic activists without working-class American youth getting their hands dirty. Until the 1989 U.S. invasion of Panama, things went totally underground for the better part of a decade, public reaction to Vietnam being a prime reason for this shift in intervention. But until coming across Hearts & Minds, I had never seen Vietnamese citizens themselves speaking about what this war wasn’t (a fight against Communism) and was (the apex of an ongoing Western colonial war of genocide against a people fighting for independence and national unification.) Nor had I heard the view articulated so well by former-Sgt. William Marshall, who lost an arm and a leg and was furious for what his country had drafted him to do in the name of, well, access to markets and natural resources. In many ways, it reminds me of Studs Terkel’s book “The Good War”: An Oral History of World War II, which serves as a compendium of human experiences across the board, the quotations around “good war” intentionally ironic. In the same vein, Hearts & Minds could be nested in the same, this being the warm-and-cuddly Lyndon Johnson phrase used to discuss what needed to be done for victory.

The film, shot just as the war was winding down, is a fast-paced compilation of interviews without narration. This was a very rare approach for a documentary on war. Newsreel style was still the norm; think the BBC’s World at War series and Laurence Olivier’s refined narration. By contrast, Hearts & Minds was honest and matter-of-fact, attempting to soften the conflict for no one. It reminds the viewer that war is also about human remembrance and raw emotional experience, not large tactical arrows outlining which division went where and why. The participants run the gamut to policy makers to people on the street, both in America and Vietnam. Infamous “hawks” like Kennedy-aide Walt Rostow openly belittle and insult Davis when he asks for an honest accounting of the conflict’s origins, saying that rehashing that is “pretty goddamn pedestrian stuff at this stage of the game.” He is but one of several who openly assume that their version of the war is the only one in existence, the only one that matters, the only one scholars need concern themselves with for the historical record. Luckily, there are interviews with Daniel Ellsberg (leaker of the Pentagon Papers), Barton Osborn (CIA agent who quit and blew the whistle on covert operations), and a host of others who tossed their bureaucratic careers aside to speak out against the injustice they’d helped to sustain in some way. Alongside these are the stories of two U.S. servicemen: Randy Floyd, an air force pilot who flew 98 bombing missions; and Lt. George Coker, a returning POW who had just spent the majority of the war in captivity. Through great editing, their own perspectives unfold gradually, scene by scene, as do those of dozens of others, like Detroit-born William Marshall, and peace-activist Bobby Muller, who would go on to found the Vietnam Veterans of America.

Most intense are the scenes with the Vietnamese, all of whom spoke up despite very real dangers for doing so (the war was still going on during early filming.) There are the victims: the coffin maker, who looks over his shoulder while speaking; the two sisters, whose prolonged silence and sadness at the end of the scene pushes an intensity onto the viewer which is almost unbearable; the Catholic and the Buddhist, both aligned in their views on the Vietnamese struggle for independence; the angry, grieving father who demands an explanation of what he had ever done to Nixon for him to come there and murder his family; the man who says to a friend, after looking at the camera, “Look, they’re focusing on us now. First they bomb as much as they please, then they film.” Then, there is the lavish country club banquet of the South Vietnamese capitalist class, the recipients of the billions in American foreign aid pouring in, one of which makes the incredible admission that “We saw that peace was coming, whether we liked it or not.” The comment is astounding, delivered without a pause, and really says it all. U.S. corporations can be seen encroaching throughout Saigon: Sprite trucks, Coca-Cola plants, toothpaste billboards with smiling Western women, even the ridiculously out of place Bank of America. Eerily, CBS logos, intended to be a “ubiquitous eye that is watching all”, are ordered left on the bodies of Vietcong corpses by soldiers in the field as an ominous calling card.

In the end, what is so relevant and sad about Hearts & Minds today is the fact that little has changed. The fabrications for foreign invasion by American policy makers continues. Consecutive administrations still lie to keep up some modicum of popular support. The jingoistic hysteria following 9/11 was nothing new, nor was the xenophobic nationalism that accompanied it. Even General Westmoreland’s racist quote has now been uttered in a thousand variations over the past ten years, just replace “Oriental” with “Muslim.” But perhaps most telling are the prescient closing words of ex-bomber pilot and activist Randy Floyd when asked what was learned from it all: “Nothing. The military doesn’t realize that people fighting for their freedom are not going to be stopped by changing your tactics, by adding more sophisticated knowledge. Americans have worked extremely hard not to see the criminality that their officials and their power makers have exhibited.”