“You can describe Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour as Faulkner plus Stravinsky.” — Jean-Luc Godard, 1959

Given the rise of the documentary form in the second half of the 20th century, it seems somehow fitting that the film that would come to define modernism in narrative cinema began its life as one. It was to be called Picadon–“The Flash”–and was to be the first French/Japanese collaboration on Hiroshima’s devastation by the A-bomb. It was a risky proposition. Impossible to imagine today given its cultural ubiquity, but in 1959, the last thing anyone wanted to talk about was World War 2. Even the Holocaust itself was taboo and beyond the realm of popular discussion until a film by Alain Resnais called Night and Fog premiered in 1955, a stark, harrowing documentary that has lost none of its punch in the last sixty years. It was this work that caused the project’s producers to approach Resnais, convinced that he could give the same treatment to the catastrophic event that helped launch the Cold War. What they got, however, was something different and entirely unexpected. What they got was the first modernist narrative masterpiece of postwar cinema, Hiroshima Mon Amour.

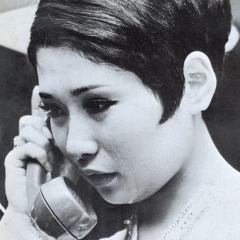

Why Resnais decided to abandon a form, the documentary, in which he had just experienced such a resounding success is a bit of a mystery, especially since he had never directed a fictional feature film before. It is clear from his own reflections that he had grave doubts going into the project, right up to the flight to Japan with cast and crew, wondering if the entire undertaking would end up a colossal failure. Given the script with which he was working, and the fact that he was determined to alter very little of it to suit conventional narrative form, it is easy to understand his anxiety. After all, this was not a love story that embraced the viewer, quickly provided familiar stereotypes, and proceeded into a three-act, run-of-the mill plot of conflict with tidy resolution. No, this was something weird, something that made up its own rules, something that pushed the audience to places it had never been before. Hiroshima Mon Amour would be the first of his many collaborations with great writers, this time with Marguerite Duras. Having made an impression in French literary circles with her novel Moderato Cantabile, with its odd shifts of time and space, Resnais contacted Duras and asked if she would be interested in writing a script. Following a few brief conversations, Resnais gave Duras complete authorial control over the finished screenplay, even in light of the fact that she had never written for film before. They decided the film would be about the bombing, yes, but more importantly, about a 36-hour love affair between a French woman and a Japanese man, about the conflicts between memory and present, about the trauma of the past and its ongoing influence over one’s life. Duras herself, as it would come to be known in her later works, such as 1984’s The Lover, had been deeply affected by a teenage affair with a 30-year-old Chinese man in French-Indochina, and it is almost impossible not to spot the emotional debris of that experience in the female lead, played by Emmanuelle Riva. Although one of many films derived from the works of Duras in the 1950s-60s, it is the only one imprinted deeply with her sense of self, where her ideas are embedded and crafted carefully within the script and not a watered-down attempt at transferring her complex literary rhythms into a conventional and linear film narrative. Later, when she would try her own hand at directing, her scripts suffered from a slowness and lack of action that is absent in Hiroshima Mon Amour, which speaks to the pair’s respective strengths as artists: Duras handling the big philosophical ideas; Resnais and his editor skillfully tying the disconnected bits together.

The narrative itself is broken down into five distinct sections. The first, running 15 minutes into the film, is the most abstract and disorienting, a brilliant montage of image and sound: intimate shots of hands caressing skin; historical images of bomb-burned flesh; a series of tracking shots through a Hiroshima memorial museum; a B-grade Japanese re-enactment film from the late 1940s; all overlain with two voices, whose identities are withheld for the entirety of the sequence. It is a testament to his faith in Duras’s craft that Resnais did not attempt to move this section elsewhere within the story. Few films in the history of cinema had ever demanded so much of an audience, denying them framework or foundations for a quarter of an hour, without any anchor apart from the fragmented sentences and how these comments relate to the action shown on screen. As this section ends, a more linear narrative begins, but one which is constantly shifting between past (the woman’s traumatic remembrances of occupied France and her German lover in Nevers) and present (the 36-hour affair with a stranger in Hiroshima, played by Eiji Okada.) One of Duras’s greatest gifts as a novelist is that of dialogue, and Resnais wisely allows her the freedom to toy with language and meaning in much the same way as she does in her fiction. Contemporary filmmakers, such as Wong Kar-Wai with In The Mood For Love, borrow heavily from the look and feel of Hiroshima, particularly the tendency for private moments to reveal themselves in public spaces, albeit public spaces that are vast, isolated, and devoid of a public. A peculiar and elusive sense of dread permeates the film, perhaps reflecting the fact that, at any given second throughout the late 1950s, hundreds of bombers were circling the globe 24-7, all filled with nuclear payloads that could be dropped on a moment’s notice. Today, this fact would strike many as nostalgic and darkly comical, but given the Strangelove-esque revelations of close-calls and technical snafus that have come to light in recent years in both American and Russian archives–from bombers breaking apart in midair over the Carolinas, to malfunctioning Soviet first-alert systems in Eastern Europe–this dread was more than justified.

Interestingly, although it makes no bold political statement, Hiroshima Mon Amour was kept from the main competition at Cannes in 1959 due to its content. Those running the festival were concerned about upsetting the United States and gave the film a separate slot, where it garnered accolades and eventually earned the International Critics’ Prize. It ended up being the runaway hit of the festival, along with Truffaut’s first film, 400 Blows. Resnais was older and not part of the French New Wave clique, and yet, Truffaut, Godard, Roehmer, and other directors proclaimed it the most important film yet of the postwar period, predicting then that it would still be watched and discussed in thirty or forty years time.