by Jim

“Shepitko’s work is disturbing and, with each passing film, it becomes more disturbing, rather than affirming. Or if there is affirmation, it is of a strange and macabre sort – the eeriness with which her work points with increasing urgency, and seeming acceptance, to the death that befell her accidentally.” — Barbara Quart, Between Materialism and Mysticism: The Films of Larisa Shepitko

The German nazis’ genocidal war against the Slavic people lasted from June 1941 to May 1945. From the outset it was a racist war of extermination modeled on the U.S.’s genocide of Native Americans. By the time the Red Army reached Berlin and put an end to it, the nazis and their fascist collaborators had murdered around 25 million Soviet people, 18 million of those civilians. That’s roughly 17,000 people per day (or five “9/11″s), every day, for four years. Belarus in particular was a living hell. The 1976 book Out of the Fire, by Ales Adamovich, is a compendium of oral history transcripts given by those who survived, some of them the only living witnesses to the slaughter of their entire communities. Not surprisingly, nazis loved “big data” and used it to conserve killing resources and track progress towards their 75% depopulation goal. As one 1941 report from Borki states:

“705 persons were shot; 203 of them men, 372 women and 130 children. Expended during the operation: rifle cartridges — 786, cartridges for submachineguns — 2,496.”

To save ammunition, hundreds at a time were locked in barns and schoolhouses and burned alive, with the bullets saved for those trying to escape. Other “resource friendly” killing methods included dumping people alive down wells and bayoneting babies; for the latter, Belarusians speak of S.S. soldiers wearing butcher smocks to keep their uniforms clean. Some “humanitarian” nazis actually felt they were considerate in their killing, letting family members decide among themselves who would be shot into the open pits of bodies first. The German army provided lots of alcohol for workday consumption to make shooting women and kids easier. In Out of the Fire, multiple survivors recall how much laughing some Germans did, sometimes turning up the music on truck radios to drown out the sounds. Over 550 Belarusian villages were destroyed and their inhabitants murdered, or sent back to Germany as slave labor. Those who could fled into the woods, grouping with others and forming partisan bands that conducted sabotage of enemy supply infrastructure, assassinations, and full-scale attacks when possible, tying down nazi manpower and resources that helped lead to their eventual defeat. This is the background for Larisa Shepitko’s dark masterpiece The Ascent, released by Mosfilm in 1977.

I say all this because the film doesn’t. Apart from one brief gunfire scene and the remains of a razed home (its clean laundry eerily blowing in the breeze), The Ascent is devoid of action sequences common to many war films. After all, Soviet audiences knew the gory details, and millions still had acute PTSD from their experiences. They didn’t need the adrenaline rush, they needed some added Dostoyevsky. Or, in the case of The Ascent, also some Christ.

Larisa Shepitko was raised by her mother in rural Ukraine and came to Moscow at 16 on her own accord to enroll at the Cinematography Institute, where she worked under one of her idols, the elderly Alexander Dovzhenko, best known for silent classics Arsenal and Earth. Her first film, the graduate project Heat, owed much to her mentor. Like him, she was concerned with landscape and natural surroundings, portraying those in ways that are mystical, unsettling and often dangerous. Scholar Jane Costlow says that, for Shepitko, “Dovzhenko represented integrity and allegiance to film as a vehicle for conscience; despite enormous ideological pressure in the 1930s and ’40s, he had continued making films of artistic value, many of which incorporated elements of visual lyricism and Ukrainian culture” (Costlow, 76). Scholar Barbara Quart says Shepitko’s work “aims for largeness, and her refusal of mediocrity, or ironic views of flawed human life, is what distinguishes her, both philosophically and professionally” (Quart, 11).

The excellent follow-up Wings (1966) becomes both an examination of generational conflict and a poignant look at the role of a woman veteran in postwar Soviet society. Russian women had a history with airplanes and flight; in 1938, a trans-Siberian distance record was set by pilots Marina Raskova, Polina Osipenko, and Valentina Grizodubova which made them national superstars and led to an influx of girls joining flight clubs. When war broke out, Raskova spearheaded the creation of fighter and bomber regiments for women, one of which was the infamous “Night Witches”, who made insanely dangerous bombing runs at night in obsolete biplanes. Shepitko’s Wings protagonist, a former pilot now stranded in an unfulfilling but comfortable Thaw-era educational bureaucracy, seems to long for those years and no longer fits into society. But resolutions are murky in Shepitko’s work, never maudlin and often confusing. The follow up, You and I, dealt with unhappy people abandoning their lives and searching for meaning elsewhere. It ran into problems with the censors and was heavily edited.

Her inspiration for The Ascent came during a seven-month hospital stay in 1973, from a spinal injury and concussion while pregnant. There, she read the novella “Sortinov” by Vasil Bykau and in its pages found key philosophical questions that went far beyond stereotypical war literature tropes about duty and sacrifice. Indeed, Bykau drew direct parallels between his partisan characters and the story of Jesus and Judas. Shepitko incorporates these elements into her film, albeit with some changes. Scholar Jason Merrill discusses these religious differences between book and film in a 2006 article, and he says these elements were toned down by Shepitko in her script. Rather than being a historical piece, he says that she wanted her film to “answer modern-day questions” and called the film “my Bible” and defined its genre as “neo-parable” (Merrill, 149). Shepitko felt it went “beyond a war picture” and that it was directed “at our own days” (Costlow, 87). Thus, The Ascent was a film that represented choices for this generation, for right now in 1970s Soviet society.

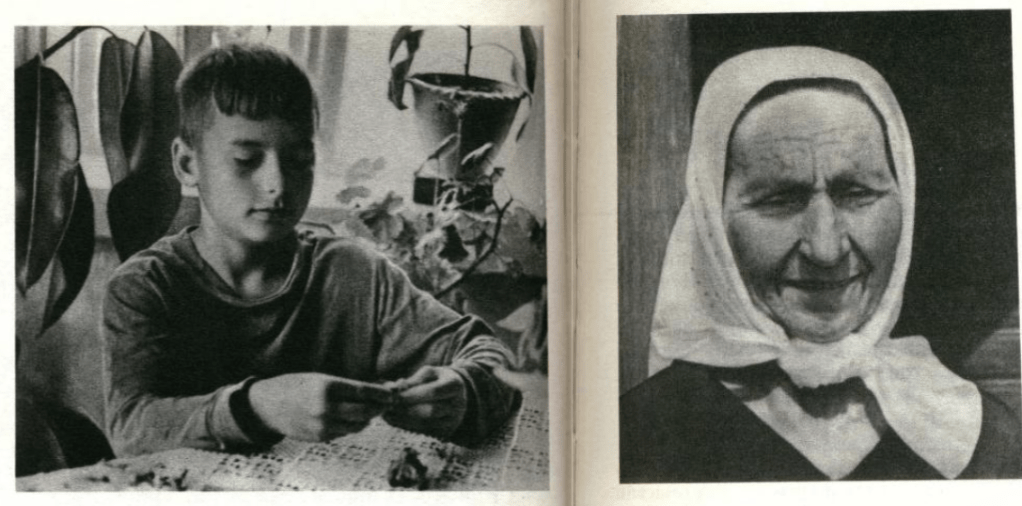

Maybe this was because she knew the young were growing increasingly disconnected from the “Great Patriotic War” and the scourge of fascism, or else were tired of hearing about it. In aforementioned Out of the Fire, as the old detail their horrible accounts, the young pace in the background, sighing heavily, bored or doing chores. In the book’s most surreal moment, one boy sits by an elderly relative and assembles a toy plastic model of nazi soldiers as she is speaking her genocide trauma story to the authors and their tape recorder:

The Ascent is a film about choices, and the more you parse them, the more complicated they become. Plotnikov’s “Jesus” doesn’t turn the other cheek, he strikes people and says his only regret is not killing more nazis. Gostyukhin’s “Judas” spends the first half of the film saving his ill-equipped comrade from death, dragging him with torturous effort through snowy underbrush. The tenderness of the “warming” sequence only amplifies the psychic break at film’s end, with its fourth-wall-busting snapshot of prolonged suffering and layers of dissonant Germanic and Russian voices (“I want to eat”) stacked upon Alfred Schnittke’s dark score.

In 1979, while shooting her follow up film Farewell to Matyora, Shepitko’s life ended tragically with a car wreck that also killed four of her crew. As she’d feared many years earlier in the hospital, The Ascent would indeed be her last film, a neo-parable testament to her Dostoyevskian worldview. The year before her death, it swept the 1978 Berlin International Film Festival, winning the Golden Bear top prize and other awards. The loss to Russian cinema was profound. Farewell would be finished by her widower Elem Klimov, who would soon dump his grief into the last great Soviet war film, Come and See (1985). He would champion her work for the remainder of his life, making the beautiful short documentary film Larisa (1980), in which she speaks frankly of the slippery, dead-end slope of selling out:

Every day, every second of our life prompts us to fulfill our everyday needs by making some kind of compromise, maneuvering, keeping silent, knuckling under just for now. One might say, well, we must be flexible. That’s what life demands of us. Everybody does it after all. But it turns out that while everyday life seems to let us cheat for five seconds and then make up for it, art punishes us for such things in the most cruel and irreversible way. You can’t make a film today just for the money. They say to themselves, “I’ll make a second-rate film. I’ll bend here. I’ll say something they want to hear. I’ll try to please these people. I will let it slide. I’ll tell a half-truth. I won’t speak up. But, in the next film, I’l make up for it. I’ll say anything and everything I want as a creative person, as an artist, as a citizen.” It’s a lie. It’s impossible. It’s pointless to deceive yourself with this illusion. Once you have stumbled, you will not find the same right road again. You’ll forget how to get there. Because, as it turned out, you can never step into the same river twice.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Adamovich/Bryl/Kolesnik. Out of the Fire (Я з вогненнай вёскі / Ia iz ognennoi derevni). Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1980.

Costlow, Jane. “Icons, Landscape, and the Boundaries of Good and Evil: Larisa Shepitko’s The Ascent (1977).” Border Visions, Scarecrow Press, Incorporated, 2013.

Merrill, Jason. “Religion, Politics, and Literature in Larisa Shepit’ko’s The Ascent.” Slovo (London, England), vol. 18, no. 2, 2006, pp. 147–62.

Quart, Barbara. “BETWEEN MATERIALISM AND MYSTICISM: The Films of Larissa Shepitko.” Cinéaste (New York, N.Y.), vol. 16, no. 3, Cineaste Publishers, Inc, 1988, pp. 4–11.

“It goes in circles.” – Bruno S.

“It goes in circles.” – Bruno S.