by Jim Bunnelle

“The world is very ill. The world needs to heal the seas, the rivers, the environment, society, money. It must heal itself. We’re all ill. The artist must react. The artist must be a healer. Cinema must be some sort of revelation. Audiences should not identify with a hero who is generally a pervert. James Bond is a pervert. Superman is a pervert.” – A.Jodorowsky

Since the Dune documentary came out in 2013, so much ink has been spilled on Jodorowsky that it is hard to remember a time when it was not so. Today The Holy Mountain is psychedelic canon, but in the pre-Internet era it was nearly impossible to find, at least in the U.S. The tape I saw in 1991 was bootlegged from a Japanese LaserDisc and sold by Video Search of Miami. They were a sort of renegade Facets (the more reputable rare video lifeline based in Chicago), specializing in Italian giallo and obscure spaghetti westerns, Soviet sci-fi, and Asian ghost stories. They’d send you a janky stapled catalog in the mail every few months. You picked your films and ordered by phone or snail mail, and then they dubbed them for you from their master copies onto a blank videocassette, for a $25 flat fee. The critical success of 1989’s Santa Sangre didn’t really improve things, and this dearth of legal availability would plague Jodorowsky’s back catalog for years. Even after DVDs came out, nothing saw a legit release early on except for Fando Y Lis. According to his new commentary, this was intentional, part of a lingering decades long beef between Jodorowsky and Holy Mountain rights-holder Allen Klein. Jodorowsky now admits to illegally distributing his own film during those years just to keep it alive, which resulted in legal action against him.

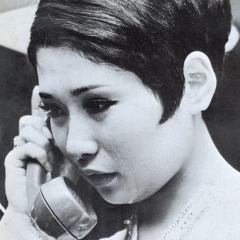

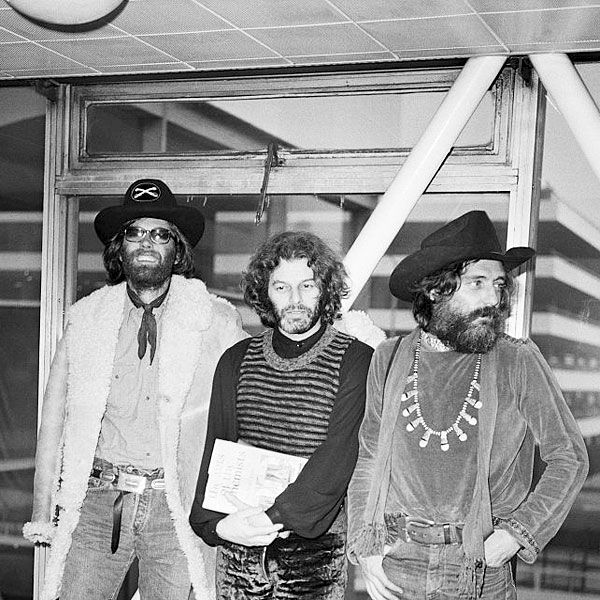

Most late-1960s U.S. counterculture films once lauded as milestones haven’t aged that well. There’s no Z or Weekend. Easy Rider in particular is more often discussed in terms of what it did for independent U.S. filmmakers, not for its content, which, for all its “we blew it” death trip fatalism, tends to reinforce Western expansionist worldviews and prioritize white male freedom fantasies. Jodorowsky, who was friends with director/star Dennis Hopper, hated conventional 3-act plots, and his feedback on the first cut of Easy Rider‘s follow-up The Last Movie resulted in Hopper making disjointed experimental edits that likely doomed the film commercially. For this time period, from 1970-71, Jodorowsky was a bit of a rock star in the U.S. and U.K. John Lennon and Yoko Ono saw El Topo on the advice of a friend and approached the director about financing for his next work, which would come via the bleeding cash cow of Apple Corps. George Harrison originally intended to play the part of the thief “Jesus figure” whose story starts off The Holy Mountain, but Jodorowsky refused to remove a nude scene so he withdrew. The fact that he prioritized a 5-second anus-washing scene over casting one of the biggest pop musicians on the planet does give credibility to the director’s claim that artistic vision is worth more to him than money.

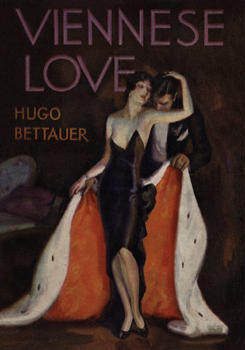

The films takes its visionary point of origin from the unfinished surrealist novel Mount Analogue by René Daumal. Jodorowsky, who did not drink, smoke, or do drugs, took LSD for the first time before filming began, under the advice and guidance of Oscar Ichazo, founder of Arica Training. In Mexico, he lived collectively with the cast in a house for two months before shooting started, sleeping four hours a day and doing exercises and hallucinogens. There was only one trained actor among them, Juan Ferrara. Jodorowsky does not elaborate on his casting decisions except that they were honest and true to life, thus the architect was an architect, the lesbian a lesbian, the millionaire a millionaire. The entire cast ate psilocybin mushrooms on camera for one scene where they needed to appear hyper-emotional. According to Jodorowsky’s commentary, two actors were trans, one of which later transitioned, Bobby Cameron from the San Francisco Cockettes, whom he calls “the most beautiful transvestite I’ve ever met.” Jodorowsky had befriended artist Nikki Nichols at Max’s Kansas City in New York; Nichols worked on the elaborate set design and acted as one of the eight seekers. On the topic of these sets: “My budget was low, but I wanted a grandiose film with grandiose sets. So I would film real locations and add something to make them a bit unreal.” Many of these impromptu stages were in public spaces in Mexico City; no permits were obtained, the cast and crew would quickly set up and shoot. Some of the extras they hired resisted what was being asked of them, and one man in the “gas-mask soldier dancing” sequence put a gun to Jodorowsky’s chest and threatened to kill him. These conflicts continued. Eventually, “two-thousand people marched and compared me to (Charles) Manson and said they wanted me out of Mexico. I fled to New York with the footage after a paramilitary group called The Hawks came to my house in the middle of the night and said they were going to kill me and my family.”

Not surprisingly, it is this same fascist militarism that is criticized within the film’s imagery. Above all, the 1968 Tlatelolco Massacre, where hundreds of students were murdered by the government while protesting the Olympics, still hangs heavy in the air throughout several surreal sequences, with birds flying from gunshot wounds and blood squirting through strange applied cranial tubes. Arms manufacturing and western cultural imperialism are skewered equally: the de-Marilyn Monroe-ing opening sequence; the horde of Minnie Mouse children; the body art assembly line and religious guns customizable with crosses, menorahs, and Buddha statues. The nine disciples themselves and their affiliated “planets” are open to many levels of interpretation, as is the abrupt ending that the cast apparently disliked (his idea to superimpose his actual home address for feedback on the film’s final shot was sadly discarded.) Mexican sculptor Felguerez created several amazing pieces, including a giant machine that births a baby machine. Like other elaborate constructions and detailed shot set-ups, all are given mere seconds of screen time. Cinematographer Rafael Corkidi, who’d collaborated with Jodorowsky on his previous works, created striking and studied compositions. His camera becomes less static and more handheld cinéma vérité for the final half, a switch Jodorwsky says was intentional and meant to signify the seekers’ shifting emotional states.

From 35 hours of footage shot, much of it was unusable. Famous Mexican editor Federico Landeros came to New York and created the final cut. Mexican sound artist Gavira improvised post-production effects, his work so impressing William Friedkin that he hired him for The Exorcist, for which Gavira won an Academy Award. Jodorowsky brought in Free Jazz trumpeter Don Cherry to compose the score. None of this helped its box office success. The Holy Mountain was a financial and critical disaster and went unclaimed by Mexico’s cultural ministry due to its objectionable content. This was fine and even expected by the vagabond Jodorowsky, who has been quoted as saying, “My country is my shoes.” It soured his relationship with Allen Klein and ultimately killed any chance for getting Dune made. He would not release another movie for which he had full creative control until Santa Sangre, some 15 years later. Today, at 94, the time that he was so ahead of has embraced him, and he has lived to see his reputation flourish among a generation who understands his philosophical ideas of filmmaking:

“When you go to the cinema and are treated like a 12-year-old child, you have a good time, but you come out more stupid each time. Cinema is making audiences stupid, it’s treating them like babies. I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to wake people up. I wanted to wake up a society that has been ill since the Middle Ages.”

Jim