by Jim Bunnelle

In Tokyo Boogie-Woogie: Japan’s Pop Era and Its Discontents, Hiromu Nagahara talks about western influences in Japanese pop music emerging 100 years ago. Jazz journeyed back over the Pacific on steamers by citizens traveling abroad, first in sheet music form, and then as 78s. It was a woman singer named Sumako Matsui who got it all going, in 1914, with a shellac side called “Katyûsya No Uta” which sold an unheard-of 20,000 copies. It was the beginning of a genre called ryûkôka (‘fashionable songs’). The trend continued into the 1920s as the recording industry matured and began cross-marketing music and cinema, with Chiyako Sato’s title track from the film “Tokyo March” so successful, it caused one critic to worry that “the taste of the citizens of Tokyo will become depraved beyond salvation.” As in the West, patriarchal fears of feminine empowerment were palpable as modernity and capitalism upended traditional gender roles. Japan’s militarist expansion from 1936-45 resulted in the banning of western music, but America’s postwar occupation brought Kasagi Sizuko’s runaway hit “Tôkyô Boogie-Woogie” whose lyrics incorporated words like ukiuki (‘buoyant’) and zukizuki (‘throbbing’) to rhyme with boogie-woogie.

Television and radio were key to the dissemination of imported rockabilly and surf music. The Ventures visit in 1962 is often referenced as a key moment in Japan on par with The Beatles landing at JFK in America. Japanese kids went wild for this new sound, dubbed ereki bûmu (‘elec boom’). Post-British Invasion, it became gurûpu saunzu (‘group sounds’), with vocal harmony and beats taking center stage. Although women were largely absent from these bands, they continued to be driving forces in enka and kayōkyoku, the two genres that had diverged from ryûkôka. Enka was ballad-centric, traditionalist, and has been compared to the Blues due to its melancholic tone. Kayōkyoku (‘pop songs’) borrowed heavily from western melody. Just as in the West, masculine attitudes surrounding rock music continued to dominate the discourse and define the parameters of what was worthy or authentic. As much as it was used to describe, Kayōkyoku was used to deride those who sang commercialized material written by others.

The Girl Group explosion that peaked in 1963 in the U.S. never really caught on in Japan. There were a few duet teams–The Peanuts, Jun & Nene–but most women artists were solo acts until the early J-pop era. Oddly, very few covered any of the U.S. Girl Group hits so common in other Asian states, like Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore; Japanese teen women singers were more likely to cover white adult-pop-market acts like Connie Francis than black teenagers like The Chiffons. Almost all of the top artists worked with original material, written for them by songwriting teams, much like a Brill-Building arrangement. Western covers were often album filler, with few appearing as 7″ releases. One exception to this is Italian singer Mina, who was hugely influential among artists like The Peanuts, Kayoko Moriyama, Maria Anzai, and Mieko Hirota, all of whom recorded and released Japanese-language versions of her songs as singles.

Biographical information in English is limited. Japanese name order has been flipped to reflect Western conventions. Anyone wanting to know more on the above period should check out Hiromu Nagahara’s book. — Jim Bunnelle

(Soundcloud yanked most of my uploads mentioned below, sorry. Most are on YT ripped by others.)

Hibari Misora

Without question, Misora is the most famous woman singer in the history of postwar Japanese pop music. Due to the fact that she was a child star, had yakuza mob connections, and embraced kitschy stage attire, writer Hiromu Nagahara called her the Japanese equivalent of Judy Garland, Frank Sinatra, and Elvis Presley. Her first recordings mimicked rival Shizuko Kasagi’s colonialist boogie music, but the 1950 release of “Echigo Shishi No Uta” introduced a new synthesis of East and West that silenced her early critics and put her on the path to superstardom. She recorded thousands of songs in a variety of genres, mainly in the enka style. Her biggest kayōkyoku hit came out on Columbia in 1967, an A-side called “Makkana Taiyō” (Deep Red Sun), where she is backed by Jacky Yoshikawa & His Blue Comets, one of the best Group Sounds bands.

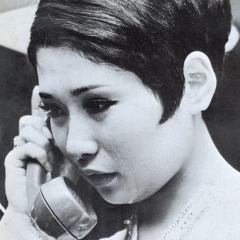

Jun Mayuzumi

That’s Mayuzumi in tears as our profile pic, getting the news over the telephone that she had just won a prestigious music award in 1968. She was massively famous and had a great vocal range and dynamic stage presence, spending the majority of her career recording for Capitol Japan. Her debut 7″ release “Hallelujah” from 1967 started a long string of great songs: “Otome No Inori”; “Angel Love” b/w “Black Room”; “Something’s Happening And It’s Saturday Night”; “First Heartache”; and “Among The Clouds” b/w “Dreaming,” a B-side that starts ingeniously with a fake skip. Few kayōkyoku house bands could compare to Mayuzumi’s lineup, as exemplified by this rare live TV performance of “Angel Love”. In 1971 she switched to the Philips label, her best single release being the sitar-tinged “Totemo Fukouna Asa Ga Kita”. She gradually shifted her sound towards ballads as the decade wore on. Since most are already familiar with the brilliant “Black Room,” listen to what she does with this traditional Japanese song “Yagi Bushi” from her 1969 album Recital, recorded live at Tokyo’s Sankei Hall, with the great Akira Ishikawa on drums. LISTEN

Akiko Wada

Another Japanese superstar of mixed Korean ancestry (like Hibari Misora), Wada’s deep bluesy sound is immediately distinguishable from all of her kayōkyoku peers. In terms of her chesty voice, and also being embraced early on by the LGBTQ drag community, she could be called Japan’s equivalent of Britain’s Dusty Springfield or Yugoslavia’s Beti Đorđević. Like them, Wada excelled at big power ballad numbers and could easily match the volume of her supporting orchestras, while always managing to swing her phrasing in a soulful way. Like many here, she also starred in films, famously playing a biker gang girl, along with Meiko Kaji, in Stray Cat Rock: Delinquent Girl Boss, from 1970, in which she sings a portion of her famed flip-side to “In The Pouring Rain,” a B-side jammer called “Boy & Girl.” Also wonderful are the subsonic trombones and fuzz accents featured on the 1971 single on RCA, “Sotsugyou Sasete Yo.”

Yumi & Emi Ito (The Peanuts)

Twin sisters Yumi and Emi Ito are best known in the U.S. for their groundbreaking role in the 1961 Toho film Mothra, where they play humanoid anti-nuclear activist fairies who can communicate telepathically with a giant radioactive moth through song. Their repertoire is more varied and international than most singers on this list. Attempts at U.S. marketing fell flat, but they were popular in Germany and Austria’s schlager scene. As for their LPs, 1970’s Feelin’ Good: New Dimension of the Peanuts is their pop-psych songbook album, with superior covers of “Spinning Wheel,” “And I Love Her,” and “Moanin’.” They appeared constantly on Japanese television variety shows until their early retirement from the industry in 1975. Although many solo singers double-tracked their voices, the Itos achieved that by default, occasionally double-tracking their backing vocals to create a cavernous choir sound. “The Woman of Tokyo” is probably their best known single, a shimmering spacey example of late 60s orchestral pop. But I am uploading a fave B-side called “Happy’s Coming” that features some cool vocal counterpoint.

Chiyo Okumura

Writing of enka at the time and defending it against charges of vulgarity, Hiroyuki Itsuki said it was “like the sound of groaning coming from someone who is being oppressed, discriminated, and trampled on; someone who is suffering and yet attempting to resist. That song is needed by people who don’t belong to a large organization, religion, or other forms of solidarity–people who are dispersed and alone” (Nagahara). Such is the sound of Chiyo Okumura, who fluctuates between smoky subtlety and a high-pitched assertive vibrato that borders on the emotionality of enka. Her layered voice could get frenetic in the bridges of songs, then spiraling into an orchestral backing track. Her first teenage releases covered French singer Sylvie Vartan, but she had better success in 1967 with a song called “Kitaguni No Aoi Sora,” a vocal rendition of a melody from a Ventures song, “Hokkaido Skies.” After that came a stretch of really great releases, including “Namidairo No Koi,” “Koigurui,” and “Koi No Dorei.” Her LPs, the few I’ve heard on Toshiba, are less interesting in terms of non-single offerings. My hands-down favorite is her 1969 A-side jammer “Koi Dorobo,” a 45 that never leaves my DJing box. It’s also found on most of her greatest-hits albums.

Tomoko Ogawa

Ogawa has been sadly neglected on contemporary anthologies, although she was prominent on girl-singer compilations back in the day on her home label Toshiba, where she was often paired with peers Jun Mayuzumi and Chiyo Okumura on joint releases. Like Miki Hirayama, she tossed in a couple of popular English-language tracks per album, her best being an electrified fuzz-laden cover of Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love” from her first LP, around 1968. She also has several great 45s that are worth tracking down. One of my favorites, which I’m uploading, is a B-side called “Futari Ni Naritai,” a smooth eruption of cool-jazz saxophone, muted trumpet, and piano fills over periodic crashing drums and Ogawa’s soaring vocal sustains.

Akiko Nakamura

Akiko Nakamura recorded prolifically for the King label, mainly singles, and also starred in several films. Her first 7″ was in 1967, “Nijiiro No Mizuumi” (Rainbow-colored Lake), where she is backed by Masaaki Hirao & All Stars Wagon (she also performed this track live in a film, backed by The Jaguars; see here.) “Suna No Jujika,” or “Cross In The Sand,” followed in 1968. She continued to record up until the early 80s. Like Okumura, she was more of a singles act, and her King LPs can get repetitive, re-using past hits as filler while neglecting her best B-sides, of which she had many. To that end, I’m uploading an energetic B-side called “Koi No Magunoria” (Love’s Magnolia) from 1968.

Kayoko Moriyama

Japanese women singers had an affinity for their Italian contemporaries, especially Mina, whose Italdisc single “Tintarella di Luna” (Moon Tan?) was covered by many, including a young Kayoko Moriyama on her early smash hit “Tsukikage No Napori.” She started on the tail end of Japan’s rockabilly/beach movie craze, her two early 10″ releases featuring covers by Western women like Connie Francis and Alma Cogan. Her biggest hit came much later, on a transcendent 1970 A-side called “Shiroichonosanba”, or “Butterfly Samba,” that came out on Toshiba and went through multiple pressings. She had one LP released around the same time, on Denon.

Kiyoko Itoh

Information is hard to find on Kiyoko Itoh. Her first LP was in 1969, called Ballads of Love, and a renowned collaboration with Kuni Kawachi and The Happenings Four followed, Woman At 23 Hour Love-In. She had a handful of singles before then, released on CBS. Our favorite is “When the Apple Blossoms,” a track saturated in warm tones that, like classic early Hibari Misora, creates a sonic mish-mash of “East” and “West.” She recorded this song twice, the second version being slower and jazzier. I have uploaded the original 45 A-side version, issued on Columbia in 1967.

Jun & Nene

Another act for which little information exists in English. The duo consisted of Jun Chiaki and Nene Sanae. My favorite song of theirs is called “O Netsui Naka”, which is a B-side released in 1969 on King Records. It is also on their first album, released that same year. Like The Peanuts, the vocal fill bits of their double-tracked voices could really make a song; in this one, listen for their cool overdubbed choral fades between lines, during the verses.

Miki Hirayama

All of Miki Hirayama’s fantastic early 45 sides–“Beautiful Yokohama”, “Noah’s Ark”, “Don’t You Know, I Love You!”–can conveniently be found on her debut album My Beautiful Seasons, issued on Columbia in 1971. Among her great LP-only cuts is her uptempo, piano-propelled cover of Dusty Springfield’s “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” which booms deeply between organ and snazzy horn blasts. Like Yuki Okazaki, she went synthy in the late 70s and continued to record and work hard into the 80s, singing on television regularly.

Mie Nakao

Nakao recorded a slew of groovy singles for Victor. Her first 7″ was in 1962, a cover of “Pretty Little Baby” by Connie Francis. French covers of France Gall and Sylvie Vartan followed. Like Kayoko Moriyama, she was a versatile singer and dabbled in jazz standards and also cinema. Her best pop 45 came out in 1968 and is an absolute double-header, the fuzzy powerhouse “Koi No Sharock” b/w “Sharock No. 1.” Both are essential but I am linking to the former because of that amazing overlapping chorus.

Linda Yamamoto

Yamamoto was brilliantly hammy. Her over-the-top stage persona was a clear forerunner of late-70s J-Pop acts like Pink Lady, and she caused a scandal with her stage outfits, with their exposed midriffs, honking bell bottoms, and overall extroverted flamboyance. Her early releases on Minoruphone are pretty run-of-the-mill, but she embraced her dancing side on the Canyon label, from 1971 onward. Since then, her career has gone through several renaissance periods and she continues to perform today.

Ayumi Ishida

Another superstar that enjoyed a long and prolific career, Ishida’s early sides on Victor are difficult to find, so I can’t comment on those. Her big break came in 1968, with “Blue Light Yokohama,” her first 7″ release on Columbia Japan, which went to number #1 on the pop charts. The powerful “Taiyou Wa Naiteiru” followed. She continued to record throughout the 1970s.

Mieko Hirota

Like Kayoko Moriyama, Hirota started her career young at the Toshiba label, covering western pop songs like “You Don’t Own Me,” “Be My Baby,” “Happy Birthday, Sweet Sixteen,” and Mina’s “Renato.” Her most interesting work came post-1965, on the Columbia label, where she matured as a singer and grew increasingly funky, with standout LPs like Exciting R&B Vol.2. In the 70s, she moved more strictly into jazz and pop standards. From the Columbia period, after Vol.2‘s blistering “Knock On Wood,” her best side that I’ve heard is undoubtedly the famed flip of “Ballad of a Doll’s House,” a track called “On A Sorrowful Day.”

Yuko Nagisa

Melodies recorded by the Ventures were highly popular among kayōkyoku singers, with new lyrics written to be sung over the main instrumental riff, similar to how jazz bop singer Annie Ross composed lyrics to Wardell Gray’s saxophone solos in 1952. Along with Okumura’s “Hokkaido Skies,” Yuko Nagisa’s “Kyoto Doll” is probably the finest example of this trend, released on Toshiba in 1970. Primarily a singer of darker ballads, there are only a few uptempo Nagisa songs from this period. I have not heard her LPs. She subsequently released a second follow-up Ventures song, called “Reflections in a Palace Lake.”

Yuki Okazaki

Okazaki was a movie star. Unlike some kayōkyoku singers who struggled to find a new style in the late-70s, she switched to the disco and boogie scene very well, with the twin albums Do You Remember Me and So Many Friends, from ’80 and ’81, still highly regarded today (see live clip here). During her earlier period, she recorded at least two LPs for Toshiba. My favorite song from that era is the B-side of her first 7″, called “Hanabira No Namida,” a spectacular acoustic mix of voice, vibraphone, trumpet, and strings.

Ouyang Fei Fei

Fei Fei was a Taiwanese-Japanese singer who started her career in 1971 with a hit on Toshiba, “Ame No Midōsuji.” From there, she had continued chart success for several years, easily transitioning into the disco scene in 1978-79. I’ve only heard one of her Toshiba albums, which is half- Japanese/half-English, containing covers of Karen Carpenter’s “Superstar” and Carole King’s “You’ve Got A Friend.” My pick that we are uploading is the splendid A-side of her second 45, the torrential tarmac drama “Ame No Eapōto” (Rain Airport).

Sources for Intro:

Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. “Twentieth-Century Popular Music in Japan.” Written by Mitsui, Tôru; edited by Robert C. Provine, Yosihiko Tokumaru and J. Lawrence Witzleben. Routledge, 2001.

Sayonara Amerika, Sayonara Nippon: A Geopolitical Prehistory of J-Pop. Michael Bourdaghs. Columbia University Press, 2012.

Tokyo Boogie-Woogie: Japan’s Pop Era and Its Discontents. Hiromu Nagahara. Harvard University Press, 2017.